Retail Investors Should Worry About Quality Of Funds, Rather Than Size

- 4m•

- 1,080•

- 21 Apr 2023

In the Financial Stability Report published on July 24, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) flagged the issue of concentration risk in debt mutual funds (MFs). Corporates and high networth individuals (HNIs) comprise more than 90 per cent of their assets under management (AUM), in contrast to equity funds, where their share stands at a more balanced 48 per cent. The predominance of corporate investors in debt funds creates certain risks.

Let us understand why debt funds become highly concentrated. “Large corporates have an AUM threshold, which means they only invest in a fund having a certain minimum size. As a fund’s AUM grows, it becomes eligible to receive funds from even larger corporates having higher thresholds. Over time, the bigger funds get bigger.

Smaller-sized funds, which are unable to meet these AUM criteria, find it difficult to grow,” says Arvind Chari, head of fixed income, Quantum Advisors.

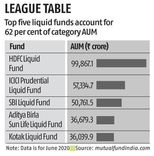

The liquid fund category, especially, is highly concentrated. At the end of June, the largest five funds (of 39 in the category) accounted for 62 per cent of total AUM (see table).

Such concentration has adverse consequences. During crises, corporates behave homogenously and withdraw money at the same time. This happened in March, just before the lockdowns began. The large drawdown by corporates, who wanted liquidity in their hands, caused volatility in net asset values (NAVs). NAVs of liquid funds turned negative for a few days — a phenomenon that created risk aversion.

Currently, there are rules to prevent concentration at the fund level. Each fund must have at least 20 investors and no investor can hold more than 25 per cent of a fund’s assets. But there are no rules to address this imbalance at the debt-fund level.

Now that the regulator has flagged this risk, what should retail investors do? Should they invest in funds having a larger AUM size, or should they avoid them? Some believe investing in larger-sized debt funds offers concrete advantages.

“Teams at large corporates monitor the funds they have invested in. This makes it unlikely that the fund manager will take unnecessary risks or deviate from his mandate,” says Arun Kumar, head of research, FundsIndia.

In a very small-sized fund of, say, Rs 100 crore, even a Rs 50-crore redemption can have a destabilising impact, while it would cause no concern in a large fund. The fund manager of a small fund has to keep a higher percentage of his portfolio in cash to meet redemption pressure, which can affect his returns. Larger funds also have lower expense ratios. This has a positive impact on returns.

Retail investors must avoid very small-sized debt funds as it is difficult to build a well-diversified portfolio in them.

Many experts believe that while large corporates should have minimum AUM thresholds, retail investors need not confine themselves to large-sized funds. In some segments, large size can even pose a problem. “The market is very deep at the shorter end, so even the largest of liquid funds will not face liquidity-related challenges. But effective portfolio management can, under certain circumstances, become difficult for a large fund in some segments, like credit,” says R Sivakumar, head-fixed income, Axis MF.

Rather than AUM, pay heed to other criteria. “In the crises that have taken place since 2008, many of the larger funds have run into trouble and have had to seek liquidity assistance from the RBI. So, more than size, pay heed to the quality and liquidity of the portfolio. Check whether the fund house has proper risk management practices in place and the manager sticks to his mandate,” says Chari.

According to Sundaram, the IT companies you bet on should have a diversified client base and not be overly dependent on one sector or company.

Direct equity investors should also pay heed to the percentage of revenue coming from digital technologies — the higher the better. They should also avoid IT companies with high exposure to verticals like travel and tourism, hospitality, and retail, which are expected to take more time to recover.